How Hillary Clinton defied the odds to lose the presidency

With most pre-election polls having forecast a victory for Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton, her loss to Donald Trump sent shockwaves across the United States, notably in the political and media circles that usually have an inside track.

Issued on: Modified:

The Democrats’ loss came as a surprise to many, including those in Clinton’s inner circle. They had a solid candidate, a career public servant with decades of domestic and foreign policy experience. They ran a good campaign with a strong ground game that got millions of likely Democratic voters to the polls even before Election Day. Their opponent was divisive, blustery, gaffe-prone and had no experience of serving in government. The smart money, it seemed, was on Clinton.

But the Clinton campaign may have made a series of false assumptions that ultimately undermined her candidacy. Paul Begala, a chief strategist for Bill Clinton’s successful 1992 presidential bid, has said that most US political campaigns can be boiled down to two essential messages: “It’s time for a change” or “Let’s stay the course”. Hillary Clinton was running on the latter, on a continuation of the policies of US President Barack Obama. Obama’s approval rating had recently hit 56%, uncommonly high for a second-term president. Most Americans are better off than they were when he took office eight years ago, when he helped the US economy begin its recovery from the 2008 financial crisis. And since then, his administration has presided over a record number of consecutive quarters of private-sector job growth.

The Democrats may have underestimated the social and economic discontent that persists across much of America, however. People in the Rust Belt states of Iowa, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, West Virginia, Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania have seen jobs dry up as manufacturing moves overseas, often as a result of the very trade agreements that Democrats like Bill Clinton (who signed NAFTA in 1993) and Obama (who signed the TPP earlier this year) have touted as being good for the US economy as a whole. The economic troubles of the industrial states preceded NAFTA, but many view the deal as having put another nail in the coffin of US manufacturing.

The 'core four' and 'undercover' voters

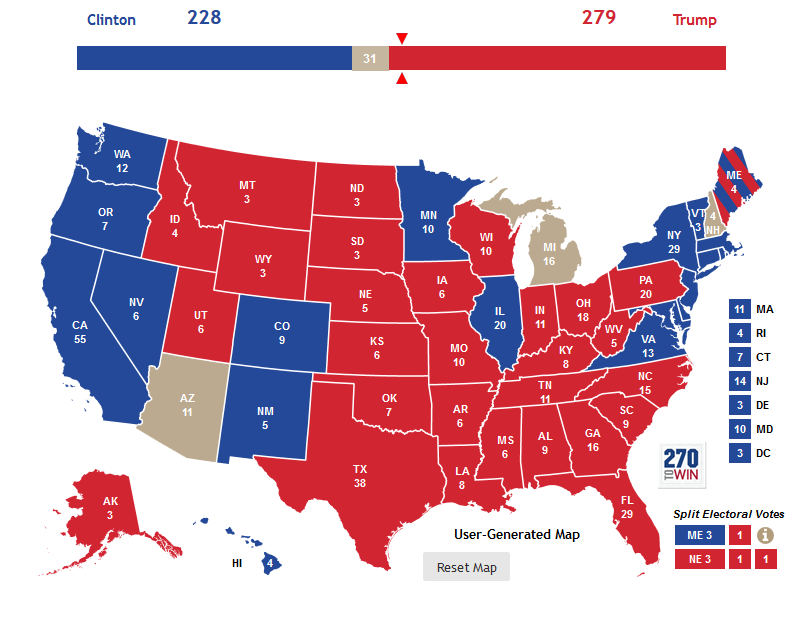

The Trump camp recognised this Democratic weakness. In response, it focused on what it called Trump’s “core four” states: Florida, North Carolina and the Rust Belt states of Iowa and Ohio. In the end, Trump won almost all of the Rust Belt states – Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania had not voted for a Republican presidential candidate since the 1980s. Identifying these states as firmly in the Democratic column, Clinton made not one stop in Wisconsin during the campaign and only visited Detroit in the final days before the vote.

Clinton won the popular vote, which stands as a testament to her and her team. But as the Washington Post noted, Clinton likely lost the election by failing to win just 100,000 votes across the once "deep blue" states of Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania.

Ironically, Bill Clinton’s success in wresting the White House from an incumbent in 1992 was partly attributed to the fact that he understood the travails of middle-income Americans, bluntly summed up by one of his campaign slogans: “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Speaking to Fox News after the vote, Trump campaign manager Kellyanne Conway said that “undercover Trump voters” had also helped deliver a victory to the Republican nominee. These supporters wanted to take the country in a “new and different direction”, she said. They viewed Clinton negatively and shared concerns over the decline of manufacturing jobs, the "ObamaCare" premium increases forecast for next year and the threat posed by terrorism.

The Trump team also recognised that the pro-change candidacies of both Democrat Bernie Sanders and Republican Donald Trump were tapping into deep public anger over what is seen by many as a “rigged” political system (which favours insiders like Clinton); a huge, well-publicised income gap; and fears over the economic future.

In this campaign environment, the “stay the course” candidate had her work cut out for her.

“Trump views Hillary Clinton as the personification of what’s rotten in Washington,” Trump’s former campaign mananger, Paul Manafort, told the Washington Post in May, soon after his candidate appeared poised to clinch the Republican nomination. “He really does make the connection between the rigged system, as he calls it, the corruption of Washington, the gridlock of Washington and the all-talk, no-action approach that Washington takes.”

“His point was that the opponent was more than just Hillary," Manafort added. "She was the symbol.”

The vision thing

But while Clinton may have chosen an uphill battle, the war was one she could have won. Obama’s message of hope and change could have been transformed into one of hope and progress, provided the Democrats had outlined a clear vision of how much things had already improved and how they planned to turn that into new prosperity – particularly for those who don't remember what prosperity looks like.

Updating this message was something her campaign arguably failed to do. Politico reported that Bill Clinton complained throughout his wife’s campaign that it was too focused on its get-out-the-vote ground game and was not doing enough to solidify a larger message or create a vision. And the Clinton slogan of “Stronger together” only really began to resonate late in the campaign, when controversy and divisiveness had become the order of the day.

When the candidates were most starkly juxtaposed – namely in the three debates – Clinton thrived, and she enjoyed a corresponding bump in the polls. She is at her best not when attacking Trump but rather when talking about the policies that she and her team have hammered out after exhaustively assessing the available research. By most accounts Clinton has an excellent grasp of public policy as well as the details that make a plan feasible.

But media campaign coverage gave short shrift to the candidates’ actual policy proposals, instead getting sidetracked by scandals ranging from Clinton’s use of a private email server to Trump’s talk of grabbing women “by the p---y”.

Policy issues overlooked

Since the start of 2016, presidential campaign coverage on ABC’s “World News Tonight”, the CBS “Evening News” and “NBC Nightly News” has contained just 32 minutes combined on policy issues, according to the Tyndall Report, which has tracked the content of the three major US nightly news programmes for decades.

ABC and NBC both racked up just 8 minutes of issues coverage while CBS offered 16 minutes.

“With just two weeks to go, issues coverage this year has been virtually non-existent,” Tyndall wrote. “Of the 32 minutes total, terrorism (17 mins) and foreign policy (7 mins) towards the Middle East (Israel-ISIS-Syria-Iraq) have attracted some attention. Gay rights, immigration and policing have been mentioned in passing.”

During the presidential election of 2012, the same three networks devoted 114 minutes to issues coverage.

This shortfall has inevitably helped Trump, who has demonstrated a weak mastery of policy issues. Trump’s campaign has posted just 15 policy proposals on its website. AP reported that there were 38 proposals on Clinton’s (ranging from Alzheimer’s to reforming Wall Street), and her campaign has said that it also released 65 policy fact sheets.

A separate report by the Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy found a similar dearth of issues-related content in its analysis of the two weeks of coverage both before and after the Republican and Democratic national conventions. Just 8% of the media's convention coverage addressed policy issues; another 3% focused on "qualifications/leadership".

Trump has “dominated coverage of the 2016 presidential election”, noted Harvard professor Tom Patterson, author of the Shorenstein Center report. “Journalists are drawn to story material that can catch and hold an audience’s attention. Trump meets that need as no other presidential nominee in memory. Trump’s politics of outrage and attack fits squarely with journalists’ story needs.”

Patterson acknowledged that Clinton's more conventional candidacy doesn't generate the catchy headlines. “[Unlike] Trump, she is not in most respects a steady source of fresh or remarkable stories."

Seeking the sensational

In a contribution to the LA Times in September, Patterson called the media out for its lack of focus and for allowing Trump to define the narrative on Clinton's policies.

“Not a single one of Clinton’s policy proposals accounted for even 1% of her convention-period coverage; collectively, her policy stands accounted for a mere 4% of it,” he wrote. “But she might be thankful for that: News reports about her stances were 71% negative to 29% positive in tone.”

Shockingly, “Trump was quoted more often about her policies than she was,” Patterson said. “Trump’s claim that Clinton ‘created ISIS’, for example, got more news attention than her announcement of how she would handle Islamic State.”

In contrast to the lack of policy coverage, Tyndall found that the CBS, ABC and NBC newscasts allotted 100 minutes since the start of the year to reporting on Clinton’s use of a private email server while secretary of state, Media Matters reported.

“[Although] Clinton’s email issue was clearly deemed important by the media, relatively few stories provided background to help news consumers make sense of the issue – what harm was caused by her actions, or how common these actions are among elected officials,” Patterson wrote in the Shorenstein report.

“And in keeping with patterns noted earlier in the election cycle, coverage of policy and issues, although they were in the forefront at the conventions, continued to take a back seat to polls, projections, and scandal.”

Part of the trend toward the sensational is driven by the marketplace concerns of media outlets, the Shorenstein Center noted.

“Presidential candidates spend their time talking about their issues and qualifications, hoping that voters will find the pitch appealing enough to carry them to victory. Reporters see the campaign differently,” wrote Patterson. “They are on the lookout for compelling stories. That perspective leads them to favor what’s timely over what’s old, what’s novel over what’s predictable, what’s sensational over what’s drab, what’s negative over what’s positive.”

Whatever the final post-mortem concludes on how a heavily favoured Clinton lost her bid for the White House, two things are already stunningly clear. First, even if the numbers say things are going relatively well, political campaigns ignore the frustrations of the economically disenfranchised at their own peril.

Second, the Fourth Estate is overdue for a round of soul-searching to determine whether – in the age of failing broadsheets and a race for clicks – the media are still performing the vital function of educating the public so that they can make informed decisions on the issues that will affect their futures.

Daily newsletterReceive essential international news every morning

Subscribe