The Great War's unsung four-legged heroes

The Great War has always been traced from the point of view of humans. With his book "Animals of the Trenches", Eric Baratay gives us the experiences of "soldiers on all fours" – the horses, dogs and other animals that battled alongside humans.

Issued on: Modified:

The French National Assembly recognised, on April 16, that animals are "sentient beings endowed with sensitivity”. The move was a symbolic recognition of a change in attitude towards animals that polls show is shared by more than 80 percent of French people.

But just 100 years ago, at the height of World War I, animals were frequently seen as mere instruments of war in the service of men.

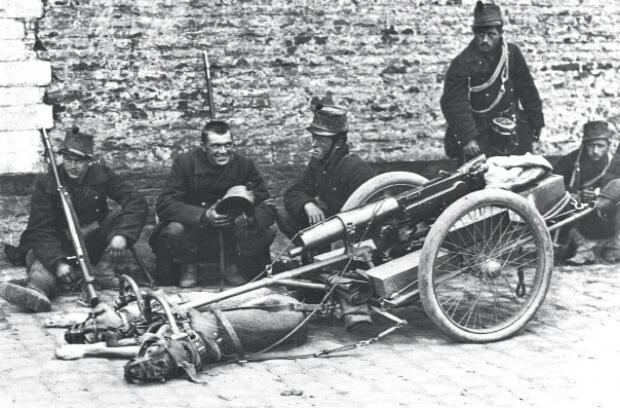

Baratay writes that these “four-legged soldiers” played a huge part in the conflict. In the hell of war, they shared the same fear, suffering and fate as their human companions. “We view this war as the first industrial war with gas, guns, planes and tanks. But there were also a lot of animals used, more than in any other conflict,” says Baratay, a professor of animal history at University Lyon 3.

Baratay writes that there would have been about 11 million horses enrolled between 1914 and 1918, including 1,880,000 in the French army alone: “The horses were really essential to the cavalry and artillery to get guns onto the battlefield. It could not be done without them. There were more animals than men in many cavalry regiments.” In a British cavalry unit, 576 horses and 74 mules were requisitioned for 549 soldiers. In an artillery regiment, 178 horses were needed for a single French battery with four cannon.

Between 200,000 and 250,000 pigeons were mobilised during the four years of fighting to carry messages or take aerial photographs. “Despite how we tend to view pigeons these days, the carrier pigeons were very modern at the time,” the historian told FRANCE 24. About 100,000 dogs were also involved in the war, carrying orders, ammunition, and searching for the injured on the battlefield.

Kindness to animals was cultural

Although the various armies all used these animals, the way they treated them varied considerably.

According to Baratay, British soldiers showed more concern for their welfare. While British riders took care to unsaddle their horses and sometimes walked alongside them if the animals were tired, the French often exhausted their mounts. French horses were also forced to stand without being released from their straps and suffered due to food rationing.

The differences were cultural: "On the British side was the idea that we are dealing with sentient beings and individual psychologies… while on the French side, it was the model of (the animal as) machine that was paramount."

Many of the Anglo-Saxon regiments even kept animals as mascots. They were accompanied by a veritable Noah’s Ark: an Irish pig, a Kashmiri goat, a chimpanzee, a lion, and even kangaroos were petted by soldiers.

While the mascots and "four-legged soldiers” were welcomed by the soldiers, other animal guests were unwanted. In the appalling conditions of the trenches, vermin thrived. “Often a soldier in the trenches was plagued by fleas, lice, and rats. They rubbed along together because soldiers very quickly understood they could not eradicate them. Initially, they could not bear them but later they became used to them. They just tried to protect themselves from being attacked.”

Away from home and cut off from their families, soldiers sometimes became very attached to their fellow sufferers. While official military accounts do not go into detail about the animals of the regiment, the testimony of the “tommies” (British) and the “fritzs” (Germans) often mentioned the horses, dogs or even cows that abounded in combat zones. Baratay says, "When, for example, a regiment was bombed, everything was destroyed. You couldn’t distinguish between the corpses of animals and humans. A shared destiny strikes you on the battlefield. You could hear both humans and animals screaming.’’

Despite the dedication they so often showed, these furred and feathered soldiers did not receive the same recognition as humans. Official decorations were awarded to British and Austrian animals, but very few were handed out by the French or Italians. Some monuments in their honour were erected in the 1920s but soon fell into ruin, long ignored by historians.

It was not until the early 2000s that they received a worthy tribute with the inauguration of the Animal War Memorial in London and a memorial at Couin, in the Somme, to animals that died in the war.

“The animal has a special place in the western world,” Baratay says. “It must be recognised that animals were victims of the conflict too.’’

Daily newsletterReceive essential international news every morning

Subscribe